Augmented Reality

Let us begin with an definition of “television” for those who may have been born post-9/11: also known as “TV” the medium was like IGTV or YouTube, minus the total freedom of choice. You had to refer to a grid schedule called a “listing” to figure out what was on – and you had to commit to a finite selection of “programs.” Around the turn of the millennium, the “tube” attempted to attract a younger audience while retaining the precious 40-year-old homemaker segment. The solution? “Reality” TV.According to lecturer Manon Renault, who specializes in the sociology of pop culture, “That’s why American reality TV shows give women the spotlight. These aren’t programs meant to attract the heteronormative male gaze. The genre is an adaptation of soap operas for the age of transparence. The late-thirties-early-forties woman is thus shown the lives of people like her, through programming aired right before dinner – when they’re likely busy doing something else.” And while other cultures have tried to import the format with varying degrees of success, the US of A remain the champions of the real-time selfie genre peddled by the Housewives and Kardashian franchises.

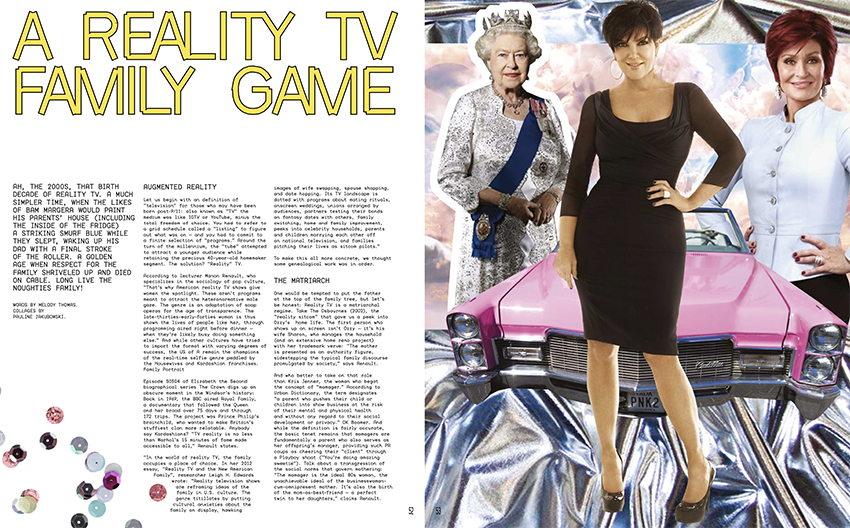

Family portrait

Episode S0304 of Elizabeth the Second biographical series The Crown digs up an obscure moment in the Windsor’s history: Back in 1969, the BBC aired Royal Family, a documentary that followed the Queen and her brood over 75 days and through 172 trips. The project was Prince Philip’s brainchild, who wanted to make Britain’s stuffiest clan more relatable. Anybody say Kardashians? “TV reality is no less than Warhol’s 15 minutes of fame made accessible to all,” Renault states. “In the world of reality TV, the family occupies a place of choice. In her 2012 essay, “Reality TV and the New American Family”, researcher Leigh H. Edwards wrote: “Reality television shows are reframing ideas of the family in U.S. culture. The genre titillates by putting cultural anxieties about the family on display, hawking images of wife swapping, spouse shopping, and date hopping. Its TV landscape is dotted with programs about mating rituals, onscreen weddings, unions arranged by audiences, partners testing their bonds on fantasy dates with others, family switching, home and family improvement, peeks into celebrity households, parents and children marrying each other off on national television, and families pitching their lives as sitcom pilots.”

To make this all more concrete, we thought some genealogical work was in order.

The matriarch

One would be tempted to put the father at the top of the family tree, but let’s be honest: Reality TV is a matriarchal regime. Take The Osbournes (2002), the “reality sitcom” that gave us a peek into Ozzy’s home life. The first person who shows up on screen isn’t Ozzy – it’s his wife Sharon, who manages the household (and an extensive home reno project)

with her trademark verve: “The mother is presented as an authority figure, sidestepping the typical family discourse promulgated by society,” says Renault.

And who better to take on that role than Kris Jenner, the woman who begat the concept of “momager.” According to Urban Dictionary, the term designates “a parent who pushes their child or children into show business at the risk of their mental and physical health and without any regard to their social development or privacy.” OK Boomer. And while the definition is fairly accurate, the basic tenet remains that momagers are fundamentally a parent who also serves as her offspring’s manager, providing such PR coups as cheering their “client” through a Playboy shoot (“You’re doing amazing sweetie”). Talk about a transgression of the social norms that govern mothering: “The momager is the ideal 80s woman, the unachievable ideal of the businesswoman- cum-omnipresent mother. It’s also the birth of the mom-as-best-friend – a perfect twin to her daughters,” claims Renault. Over the last few years (or seasons in this case), Kris Jenner has been undergoing a radical narrative evolution: at 64, she fully owns her sexuality as a menopausal woman, as well as her wild streak and her complicated past – not to mention her workaholism: “Pop culture revels in presenting multiple layers of meaning,” says the sociologist.

The father

In most American reality series, the father’s role is that of subordinate: “Reality TV really took off after 2001, as the model of the nuclear family was breaking down, and, in parallel, the man’s place within the family,” Renault suggests. So what’s the purpose of the on- screen father? The writer thinks that he is a foil that makes the mom look good in everything she does: “He’s often set up to fail in a comical manner.” Let us think back to a pre-transition Caitlyn Jenner’s attempts at explaining the birds and the bees to Kylie, or periods to Kendall. While the father is no longer master of his domain, he is nonetheless far from castrated: Masculinity just takes on a different expression. Take Snoop Dogg’s series in which the married father of three remains the sole provider. Likewise for Ozzy Osbourne, and, at least at first, Caitlyn (née Bruce) Jenner: “Caitlyn Jenner, when still known as Bruce, found an expression of his masculinity in his Olympic medals. As she gradually took on feminine traits, she dropped off of the narrative. Her role as a father was to be the foil, and when she fully came out as a woman, she became useless.”

The grandmother

Grandmothers are often completely excluded from American reality TV. This reveals itself as an inevitable side-effect of the American Dream and the melting-pot mentality: “Ethnic roots are only brought to life when the participants’ celebrity status has been made official,” according to Renault. “The Kardashians’

MJ is never designated as ’granny’. She doesn’t have the same physique and thus puts a dent in the narrative carefully constructed by the girls.” Moreover, the latter have lately taken to highlighting their Armenian roots, as if to lean into the racial ambiguity amplified by their romantic relationships – and their bodies.

The siblings

While the members of the Kardashian Klan have been mocking and tearing each down for over 18 seasons, they do show a united front off-camera: “Just like any other community, people bring each other down, but you have to show unity to the outside world. Fights and competitiveness are acceptable within the framework of the family,” Renault proposes. It is also rare to see them state an opinion on the rumors about their relationships outside of the show’s context. In Season 17, eldest child Kourtney seems to hint at wanting to leave the show. But can one remain part of the family when excluding oneself from its front-facing narrative? The answer could come in the form of Rob Kardashian’s “role”. Formerly the family’s coddled little brother, Rob practically grew off of the series. Renault: “He never found his place and, as he put on more and more weight, he didn’t feel comfortable with being shown on the show. He thus became the family failure, a pale picture of the father whose name he bears.” Another, more sexist reading: Women can’t make a man into a man. They can only neuter them.

The boyfriend

Just like any good soap opera, reality series put forth romantic intrigue that often veer towards the vaudeville, as

our heroine desperately seeks the Prince Charming with whom she will live with happily ever after. The boyfriend thus takes on one of two classic heteronormative paradigms: the Prince Charming or the Bad Boy with a Heart of Gold. The latter case was represented by the likes of The Hills/Laguna Beach’s Justin Bobby or Keeping up’s Scott Disick. As Renault points out: “It all boils down to the idea of the toxic, often violent character that the audience loves to hate. We just can’t fathom what the female character even sees in him.” Luckily, the archetype tends to get supplanted by the fiancé, and ultimately the husband.

The role of Prince Charming has become superannuated and devoid of credibility, ceding the stage to a certain vision of female empowerment that has grafted itself into the idea of family foundation. This new trait isn’t always welcomed by fans, with the rumors of a “Kardashian Kurse” that dictates that every that all of the men they date reveal themselves as toxic.

The children

Children are a recent addition to the cast, as teenagers used to be the only “young” personalities shown on screen.

But it’s only natural that, having grown up alongside reality stars, we are now seeing them turn into parents themselves: “There used to be a disconnect between Sweet 16 and Teen Mom. The paradigm of the bad mom has always held a sway over the America psyche, especially with regards to sexualized celebrities. To wit: the case of Britney Spears,” Renault expounds.

Lately, the archetype of the young mom has evolved, leading to the rise of what one could call the “Kylie Jenner effect”: “Kylie has reversed the new trend of

women who choose to push motherhood back to the end of their studies and the establishment of their careers. She became pregnant the same year she became a billionaire. But note that without such financial resources, the model doesn’t work,” Renault adds.

Enter the 80s trophy kid: While the mere presence of a child in the family unit represented a token of success, the phenomenon has now been amplified by social

media. In the age of self-mediatization, children become Disney characters in and of themselves, recurring features on their parents’ (or their own) accounts.

The half siblings

And what would Hollywood be without its network of blended families? The foremost example is the Kardashian-Jenner axis’ byzantine family tree, which made it possible for Kendall Jenner to be Bella and Gigi Hadid’s stepsister: “The function of the half-sibling is to move the story forward without intervening in the narrative themselves. Just like in Cinderella’s, they are interchangeable so that their impact is never too great.”

Foundational Gen-X author Douglas Coupland wrote in All Families are Psychotic that “people are pretty forgiving when it comes to other people’s families. The only family that ever horrifies you is your own.” It turns out that our fascination for reality TV shows helps us realize that other families’ lives may be more or less similar to our own after all. The cathartic impact that these parables have on us makes our religious dedication to them more pleasure than guilt – after all, “Kim, there’s people dying.”